Over the past few months, a new class of publicly traded companies have been vying to accumulate billions of dollars in cryptocurrencies. The next largest strategy after Michael Saylor’s Bitcoin-focused strategy is Bitmine Immersion (BMNR), chaired by Wall Street strategist Tom Lee, which currently holds about 3.75% of the ETH supply, according to data from Blockworks Research.

That begs the question. Will Digital Asset Treasury (DAT) turn its balance sheet into protocol leverage?

Thinkcracy Capital’s Ryan Watkins suggests that in principle DAT could gain substantial influence, but skeptics counter that Ethereum’s governance processes, client diversity, and stubborn “social layer” of validators make complete control impossible.

Although the issue quickly enters the realm of speculation, Watkins says it’s clear that Bitmine is in a privileged position among DATs due to its high trading volume.

“BitMine trades on average over 10 times more volume (compared to SBET) each day,” Watkins told Blockworks. “This allows us to raise funds quickly to purchase ETH, and will continue to scale.”

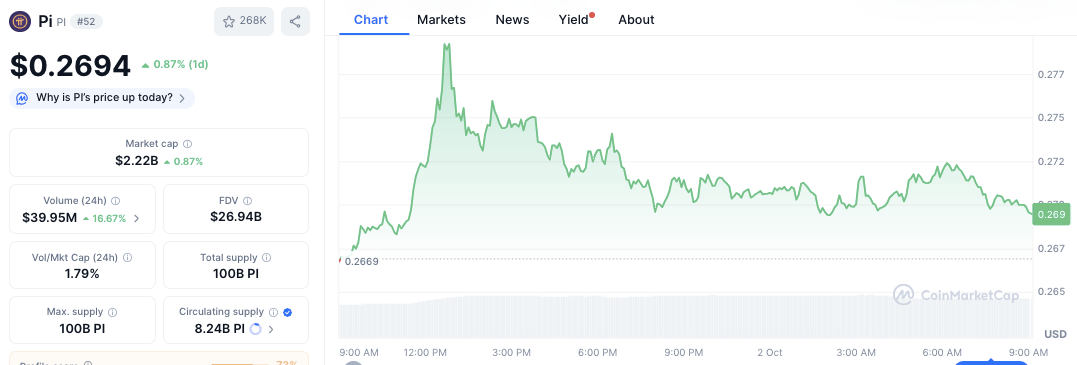

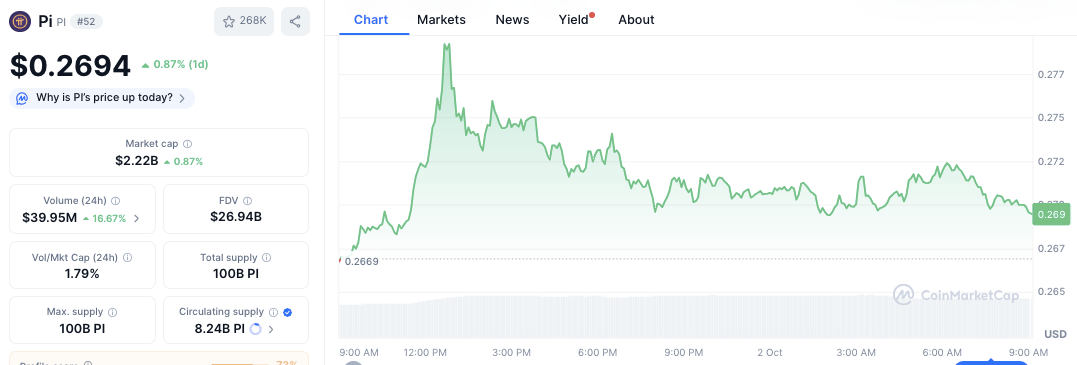

At this scale, few other ETH DATs register. sauce: Block Works Research

At this scale, few other ETH DATs register. sauce: Block Works Research

When is DAT important?

Still in its early stages, DAT is still primarily focused on ways to increase the national treasury. Watkins outlined the potential arc for well-funded DATs if the flywheel of easy capital slows.

“At some point, I think the alchemy of mNAV will stop working as well. Then you’ll see BitMine start to get more creative and proactive, like deploying ETH on-chain and starting to become a bigger player in the Ethereum economy,” he said.

The impact will most likely be cumulative indirectly, impacting application governance first. If DAT maintains nine-digit balances on Aave or any major liquid staking protocol, that view will carry weight.

“If you’re an Aave and Tom Lee has 10 to 20 percent of your deposits, you might want his opinion before making any big changes,” Watkins said.

In that case, ownership of the infrastructure may arise. If DAT starts manipulating validators, RPCs, and indexers at scale, the user called may change as parameters or client development priorities change.

Talent acquisition is also a risk. While simply hiring or starting a core development team won’t move Ethereum’s governance process, a dense cluster of researchers and client contributors under a single financial control could provide a form of soft power.

Loading tweets..

Dr. Paul Dylan Ennis, a lecturer at University College Dublin (known as Polar in X) and avid Ethereum governance watcher, is pushing in a different direction. Ethereum is not a company, and the Ethereum Foundation is not a management team.

“It’s a weird polycentric system with people who specifically chose that ethos, and it’s a little bit ideological,” Dylan-Ennis told Blockworks.

He understands the premise that “money speaks,” and with enough scale, someone like Lee could leverage his ETH holdings to shape the direction of Ethereum.

“But that is a fundamental misunderstanding of how Ethereum works culturally and structurally,” Dylan Ennis said.

Ethereum’s governance structure, consisting of AllCoreDevs (ACD) Cole, EIP editors, Cat Herders, and others, is aimed at coordinating processes, not profits. To “take over” Ethereum, DAT will need to build consensus with client teams and persuade a globally distributed base of node operators and validators to run its preferred code.

Currently, public trackers are showing more than 10,000 to 15,000 Ethereum nodes worldwide. This is spread-based, requiring you to opt-in to any changes. In Dylan Ennis’ view, this is far more cumbersome than hiring a few senior engineers.

“Ethereum is probably not a perfect example,” Watkins said, noting that the governance process is “messier” than “democracy or plutocratic governance systems where it is clear who has power (and how much power).”

“With Solana, it’s simpler,” Watkins said. “You hold a lot of tokens and you vote with those tokens. That’s the impact.”

However, he said DAT is “in a speculative incubation period and we are looking for the fastest way to expand these treasuries.” Right now, if you’re successfully scaling a DAT like BitMine, there’s no pressure to be creative with your governance. At least not yet.

Smaller Treasury departments are already conducting cutting-edge experiments. “They need to find a way to stand out,” Watkins said. So you see, for example, ETHZilla is putting hundreds of millions of dollars into the liquid staking ecosystem.

BitMine hasn’t done that yet, but it’s possible.

Tom Lee’s BitMine Immersion Technologies Inc (BMNR) leads by a wide margin in ETH holding race among DATs | Source: Block Works Research

Tom Lee’s BitMine Immersion Technologies Inc (BMNR) leads by a wide margin in ETH holding race among DATs | Source: Block Works Research

Ethereum’s immune system

Dylan Ennis’ counterargument is that Ethereum’s governance has repeatedly been more about prudence than expediency. The “immune system” for this project is a combination of processes and cultures. A rough consensus on ACD, a conservative client team across both the consensus and enforcement layers, and a membership of node operators who put ideology first and profit second.

There are no shortcuts to building social consensus around EIP reviews, client implementations, and chain upgrades. A putative DAT push would still face these bottlenecks.

Coinbase (or any key stakeholder) can provide input just like any other company, but history has shown that in trusted, neutral systems, extraordinary pressure from companies can backfire. The closest historical parallel is outside of Ethereum. In Bitcoin’s 2017 block size war, a coalition of miners, exchanges, and VCs supported SegWit2x, but it lost to user-led opposition.

Dylan Ennis argues that the most likely outcome of coercive pressure is not capture, but a hard-forked ghost chain and a reputational backlash against those who tried, much like Bitcoin Cash (BCH) today.

Stablecoin issuers and exchanges can influence which forks “win” by deciding what they support. Exactly what happened during the 2022 merger when Circle (USDC) and Tether (USDT) committed to supporting only proof-of-stake chains, starving PoW forks with oxygen. Even if governance breaks down in the future, similar collaboration dynamics are likely to emerge.

Watkins cited Joe Freeman’s essay “Tyranny without Structure” as a potential critique of Ethereum’s governance. As formal authority weakens, an informal center of gravity emerges. “It’s not clear who has the power,” he said. That doesn’t mean it lacks power.

“A strong candidate to become one of these centers is someone who holds a 10% pile of ETH,” Watkins said. In that world, influence means building alliances with larger stakeholders, such as exchanges and asset managers, and winning over the “hearts and minds” of operators in the ecosystem to get certain releases shipped.

The remedies in this essay (with clear authority) are consistent with continued efforts to refine and improve EIP/ACD procedures and suggest that Ethereum’s best defense against possible capture is more daylight, not less.

But it has to be authentic. Previous analyzes of open source software communities have pointed to similar dynamic Freeman flags. In other words, the rhetoric of openness can mask entrenched informal hierarchies. This is a useful context for evaluating claims such as “anyone can propose an EIP.”

unanswered questions

For now, Watkins sees Tom Lee’s influence as limited, in part because balance sheet expansion remains the key event. “He’s not even running a full node,” Watkins said, adding that staking through an administrator may be keeping BitMine’s ether from impacting daily client releases and parameter changes in the short term.

However, the pace of accumulation and the willingness of smaller DATs to enter infrastructure, DeFi, and validator operations makes this more than just a thought experiment.

Blockworks reached out to BitMine representatives for comment on future plans, but did not receive a response at the time of publication.

“It remains to be seen what the final state of these financial companies will be,” Watkins said. As DAT evolves from a price bet to a policy instrument, Ethereum’s norms will be put to the test in public.